On the necessity of fieldwork during a pandemic

I witnessed the Dutch lockdown from a distance because I was based in Namibia at the time for archival research, and was set to travel through southern Africa for the next couple of months. But no one can escape reality.

In March 2020 the Netherlands changed beyond recognition when an ‘intelligent lockdown’ was issued to combat the surge in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. I witnessed this sudden change from a distance because I was based in Namibia at the time for archival research, and was set to travel through southern Africa for the next couple of months. But no one can escape reality. Soon, the first infections were detected in the region and I travelled back home, on the orders of Leiden University. What this would mean for the continuation of my PhD project was entirely uncertain.

Seven months later it is time to take stock. I work at the African Studies Centre Leiden, a wonderful academic environment and the only institute in the Netherlands entirely devoted to the study of Africa. It is becoming increasingly clear that it is very difficult, and in some cases impossible, to conduct research in Africa without going to Africa. Particularly PhD students and junior researchers are affected by this – those with precarious, temporary contracts. Our research is standing still, but we are running out of time.

The importance of fieldwork

I feel that the analogy with lab work is appropriate. Without fieldwork, Africanist PhD students cannot do their research, similar to those in the sciences who need access to a lab. The university took measures to open up the labs for research after the initial ‘intelligent lockdown’ was over, and rightly so, but international travel has so far been forbidden. This has grave consequences for ongoing research projects who are dependent on foreign archives and informants.

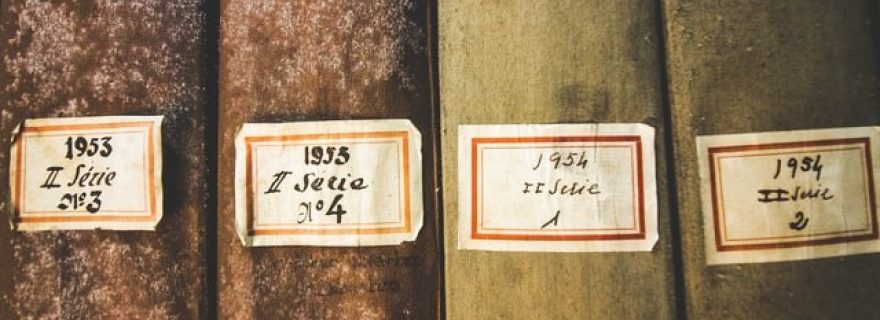

Let me give you two examples. One of my colleagues was in the early stages of twelve months of ethnographic research on queer women in Senegal, where the predominant religion is Islam. She is not allowed to return to Senegal, but this incredibly sensitive research cannot be conducted through Skype. My own PhD project deals with the international ties of liberation movements in southern Africa. I am relying on archives that do not have websites, let alone digitized files that can be accessed remotely. Some projects simply do not have obvious digital alternatives.

Especially in times of crisis, Africanist research ‘on the ground’ is important. Africanists are used to work in strained or even hazardous field settings. But academic considerations do not play a role in the issue of international travel, nor the practical argument that most places in Africa are much safer than the Netherlands, in terms of corona infections. The decisions are made by risk managers (the International Incident Team), not by university boards, and their stance is clear: no travel, no exceptions.

Extension or no extension?

I have modified my project as much as possible during the past months, just like my fellow PhD students. This is a process that takes time and is made more difficult because the future remains hard to predict. With time running out on our temporary contracts, an extension will make a substantial difference. The announcement in the summer that the university will extend the contracts of affected PhD students was thus met with relief and gratitude.

Unfortunately, it turned out that only last-year PhD students were able to apply, leaving those halfway through their projects in distress. In practice, students who have crossed the first-year milestone (like my colleagues and I) fall between two stools. We have progressed too far in our projects to entirely disband our original plans, since that would result in a year (or more) wasted, but not far enough to be eligible for a contract extension.

I strongly feel that this is a blind spot in the current discussion about how the academic community is affected by the pandemic. Together with restrictions on travel, some PhD students find themselves in a disastrous predicament. The university offers us kind, emphatic words, but no real perspective. This could be done by revoking the travel ban for urgent cases or, if this is not possible, extending PhD contracts so students have enough time to transform their projects into something else.

About Tycho van der Hoog

Tycho van der Hoog is a PhD student and member of the Service Council at the African Studies Centre Leiden. His book Monuments of Power: The North Korean Origin of Nationalist Monuments in Namibia and Zimbabwe appeared in 2019.

0 Comments